Cleopatra’s Pearl Cocktail

The story goes that Cleopatra once dissolved a pearl in vinegar and drank the mix. Apocryphal? True? In the 1950s, a historian tested it out

I’m fascinated by people’s schedules–and I’m not the only one. There’s this feeling, when you read one of The Cut’s “How I get it done” articles or watch a YouTuber’s 15-step self-care routine, that if you just made that one crucial tweak, your life would be better. You’d be optimized.

During the week of November 2nd, I learned that I’m also fascinated by people’s coping mechanisms. As we waited for the results of the US election, I know friends who stress-baked like it was March 2020. Others who threw themselves into the memes. Some just took off to the woods or on long walks to keep from checking the results every 15 minutes. To the friends not on social media, I sent texts asking how they were holding up, what they were doing to pass the time.

I survived that week via a combination of Gritty memes and reading Cleopatra: A Life, Stacy Schiff’s 2010 biography of the last queen of Egypt. Reading about the geopolitical messes of the ancients was an incredible distraction from the geopolitical mess that is 2020. And, in one of the footnotes, I found this newsletter’s paper: “Cleopatra’s Pearls” by Berthold L. Ullman.

This isn’t a scientific paper. But it is an academic paper with a science experiment. There are replicates; Ullman spent some time in a chemistry lab; and Tiffany’s (yes, that Tiffany’s) donated pearls for the investigation.

Unlike last newsletter’s paper about the bee microbiome and group membership that felt like the beginning of a new research niche, this paper is an open-and-shut operation. It is, however, a paper about confirming legendary stories with science, which is a delightfully break from *waves at the dumpster fire still going on*.

[Photo by Fernanda. A picture of the paper “Cleopatra’s Pearls” by B. L. Ullman and Stacy Sciff’s Cleopatra: A Life on my desk.]

There are so many myths about Cleopatra that it’s hard to separate fact from fiction. Many of the first to write about the last Ptolemaic ruler of Egypt were putting pen to parchment years after her death at 39. And they were writing with an agenda, wedging Cleopatra into the version of history being told by the Romans. For them, Cleopatra was manipulative and decadent, a menace to the Republic, and their stories about her reflect that.

One such story involves a pearl and a cup of vinegar. According to Pliny the Elder, a Roman historian writing about a century after the event, Cleopatra boasted to Mark Anthony that she could serve a dinner worth 10,000,000 sesterces.

Converting ancient currency into modern day values is not an exact science. One sesterce could buy you a half liter of wine in Roman times, but is that good wine or bad wine? According to one sketchy website called Global Security Org which looks straight out of early 2000s, 10,000,000 sesterces is about 3,075,000 million USD based on the current price of gold. Suffice to say, it was a lot of money for a single dinner.

Mark Anthony was incredulous, but curious to see if Cleopatra could pull off. The next evening she served a standard dinner but with one difference. Before her was placed a dish of vinegar. Cleopatra removed one of the pearl earrings she was wearing and plopped it into the vinegar, where it dissolved. She then swallowed the drink.

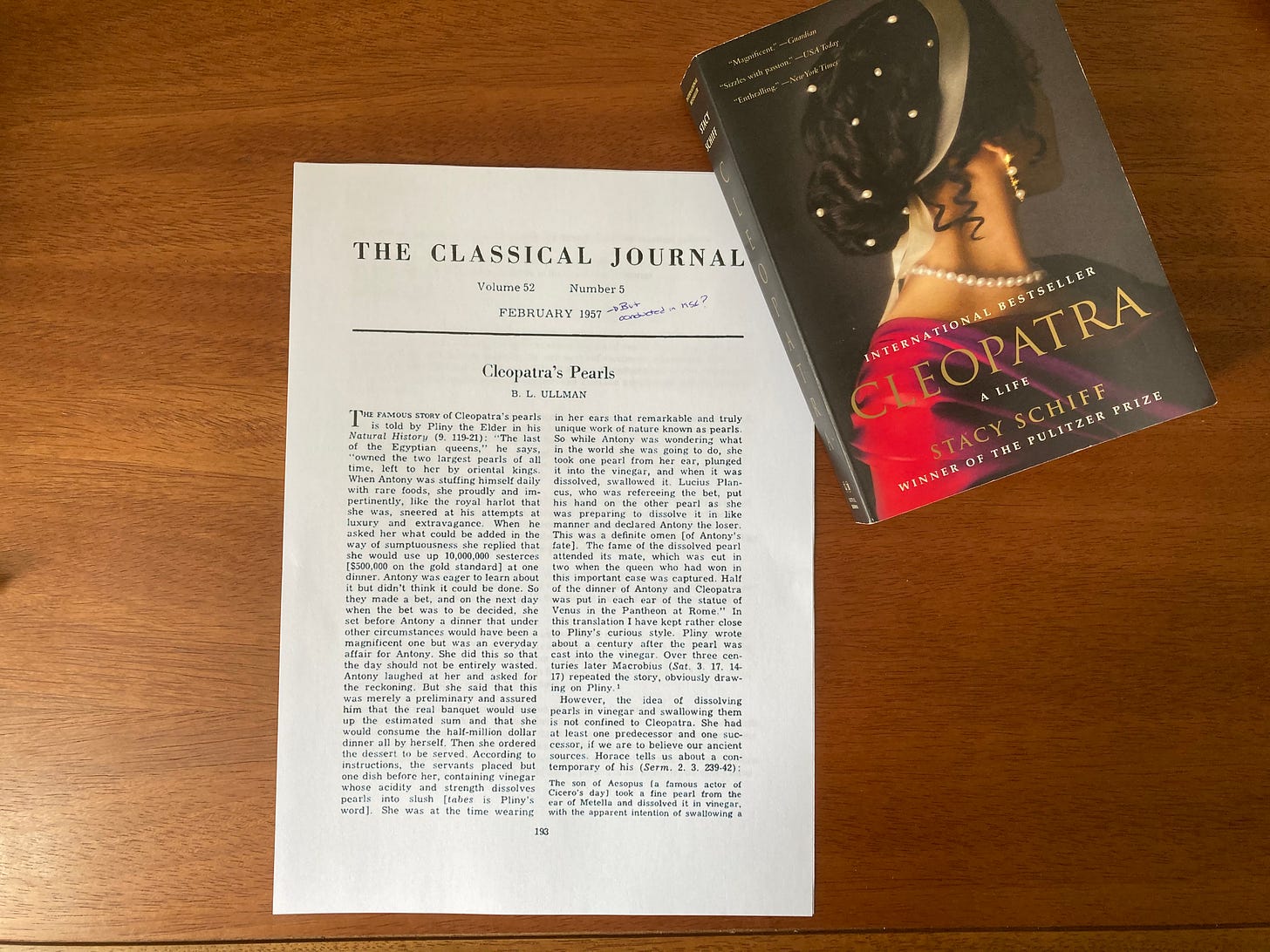

[The Banquet of Cleopatra (1743-1744), by Giovanni Tiepolo. National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. This Renaissance-era painting by Tiepolo depicts the fateful banquet where Cleopatra, shown in a peach-colored gown of a style that is not at all representative of 40 and 30 BCE when the dinner probably happened. She holds a pearl earring over a very tall glass filled with vinegar ready to drop it in. Across from her is Mark Anthony, in his red general cape. The scene is populated by attendants and revelers.]

As Ullman points out in his article, “Cleopatra’s Pearl,” this isn’t the first or only story involving a decadent individual and a dissolved pearl. Horace, a Roman poet, tells a similar story about the son of a famous actor who wanted to “swallow a million sesterces in a lump” in his Satires. Cruel Caligula was also a fan of drinking pearls dissolved in vinegar according to Roman writers.

Are the stories true? Depends on who you ask. Some historians accepted the pearl into vinegar stories, while others rejected them. Over the years, scholars have tried to add scientific objectivity to this stories, attempting to dissolve pearls in vinegar or ascetic acid with varying results. But even here there’s disagreements: some report that a pearl dissolves in boiling vinegar in eight to 15 minutes, while others say it takes hours. These scholars, however, were using pearls of different sizes.

To get to the bottom of the mystery, Ullman took a box of irregular-shaped, freshwater pearls given to him by the vice-president and gem expert at Tiffany’s and got to testing it.

Pearls are the greatest example that what is desirable to one group is not for another. When Elizabeth Taylor’s (who played Cleopatra in 1963) La Peregrina, a pear-shaped pearl that has passed through the hands of Napoleon’s older brother and the Spanish monarchs, went up for auction in 2011, it sold for 11.8 million dollars (it did come with a whole necklace though).

But for the bivalves (oysters in the sea, mollusks in freshwater) that make them, a pearl is the result of an irritant. Often a parasite, when the irritant gets in the bivalve secretes layers of aragonite (calcium carbonate) and conchiolin, together forming nacre, aka mother-of-pearl. This encases the parasite, protecting the bivalve and producing a pearl.

Technically anything can be an irritant (though, usually not a grain of sand). At the National History Museum in London, there’s even a pearlized pearlfish. Pearlfish are small fish that often hide in oysters. At one point, a pearlfish died in a mollusk and was covered in nacre.

Irritants are sometimes added purposefully. Cultured pearls are made by inserting an irritant, such as a nucleation bead, into oysters; after a year, the cultured pearl is around a centimeter wide.

Pearls are mostly made up of calcium carbonate, which reacts when in contact with acetic acid, the main component of vinegar after water. Atoms in the calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and the acetic acid (CH3COOH) rearrange themselves, producing in the end water, CO2 and calcium acetate.

You can replicate this chemical reaction at home. Pearls are expensive, but they aren’t the only thing made of calcium carbonate. Eggshells are about 95% calcium carbonate and if you drop an egg in a cup of vinegar, you’ll see bubbles of CO2 cling to the shell. Leave it alone for 24 hours and the eggshell will dissolve entirely. There’s a video on YouTube that goes through the whole experiment.

But, as Ullman and others have found out, it takes a little more effort to dissolve a pearl.

A careful, methodical experimenter Ullman is not. At one point, he lets the boiling vinegar dry off because he was off reading a detective story. At least he’s honest. Armed with his box of freshwater pearls, he conducted a handful of experiments at home:

1. Pearl in cold vinegar (unknown strength): the vinegar dried off without any impact on the pearl

2. Pearl in boiling vinegar for 33 minutes: no discernible difference, though the pearl looked “peaked”

Ullman then headed to the Chemistry Department, most likely at UNC Chapel Hill where he was at the time. Using both 5% and 8% acetic acid (same percentages as many vinegars), Ullman ran his experiment using small pearls under three conditions: boiling acetic acid, room temperature acetic acid, and with ground pearls in cold acetic acid. He had a separate experiment with larger pearls in room temperature acetic acid.

Boiling acetic acid: after 200 minutes, the small pearls were 92% and 88% dissolved

Room temp acetic acid: after 20 hours, the small pearls were 23% and 36% dissolved

Grounded pearls in cold acetic acid: completely dissolved (though with some organic matter left)

Large pearls in room temperature acetic acid: Ullman doesn’t say

Could the experiments have been conducted more rigorously? Yes. A time-course, where Ullman records the size of the pearl every one or two hours would give us an idea of the dynamics of how pearls dissolve. Repeating all the experimental conditions with the large pearls would tell us about the impact of size.

But, Ullman never tells us how many pearls he got from Tiffany’s or how much they varied in size. It’s possible that the experiments he did were limited by the number of pearls and how many there were of comparable size. Additionally, these few experiments may have been enough to satisfy his curiosity. It definitely sounds like they did. “…It is clear that the story about Cleopatra could not be true in its literal sense, though there is truth in it,” Ullman concludes shortly after his combo experimental design and results paragraph.

In short, pearls don’t dissolve quickly. They need to be coaxed, either by boiling vinegar, crushing pearls, or just letting them sit for hours.

While it’s possible Cleopatra (or Caligula, or the Roman actor’s son) did drink dissolved pearls, they couldn’t possibly have plucked one off a piece of jewelry, dropped it in a goblet of vinegar and drank it minutes later. They needed more time or more effort. Or, as some historians suggest, they may have swallowed the pearl whole, only giving the impression of dissolution.

Ullman goes on to give examples of other instances where pearls have been crushed and dissolved in other liquids. He argues that it’s possible that the dissolved pearl was taken as an antacid, like you might take Tums (made of calcium carbonate + sucrose) after a heavy dinner. If that’s the case, it’s more surprising that Cleopatra wasn’t crushing pearls and drinking them in vinegar every night. Her dinners, as described in Stacy Schiff’s book, sound like the kind of affair that would require some post-revelry Tums.

In 2010, another classicist repeated the experiment. Prudence Jones, at Montclair State University, left an approximately one-gram pearl in white vinegar (5% acetic acidic) and noted that it took between 24 and 36 hours to fully-react, leaving only some translucent gel-like material.

Jones suggests another reason for Cleopatra’s pearl-dissolving antiques: extravagant one-upping. “My dinner is more expensive than yours,” she writes.

If you were a fan of the BuzzFeed video series Worth It comparing cheap, medium-priced and über-expensive food items, this makes sense. On the higher end, the food is made expensive via ridiculous means. It’s doesn’t look good. It doesn’t even look particularly tasty. There’s no denying, however, that it’s expensive in an eat-the-rich kind of way.

The $2,000 pizza, for instance, has squid ink dough, foie gras, some fancy English cheese and black truffles from France; it’s then sprinkled with 24K gold. A $1,000 Golden Opulence Sundae has Tahitian vanilla ice cream infused with Madagascar vanilla. There’s also 23K gold sheets, chocolate sauce made from the most expensive chocolate and the behemoth is then topped with candied fruit from Paris and dessert caviar. Oh, and it’s served in a Baccarat crystal goblet you get to take with you, which is a throwback to Cleopatra who would insist dinner guests take home the gold plates at the end of the revelry.

As Ullman notes in his final paragraph, he’s happy his paper will only be read by college and high-school teachers of modest means, too poor to put his experiment to the test. “Accordingly I have no fear that I have led any of you into the temptation of emulating Cleopatra and her pearlcasting.”

Further Reading

Stacy Schiff’s Cleopatra is great. As Schiff notes, there are very few primary sources about the last Ptolemaic queen, so she tells Cleopatra’s story by providing a ton of context about the politics of the time and, when using secondary sources writing years after the fact, she discusses why they depicted Cleopatra the way they did.

As Prudence Jones mentions in her article, many painters depicted the moment where Cleopatra’s about the drop a pearl earring into a goblet. I’ve included Tiepolo’s interpretation here, but it’s always interesting to see how different artists painted the same story. This Wikipedia article has links to a number of those paintings.

There are a lot of papers about the properties of nacre (it’s super strong!) and using it as inspiration for new materials. This project for a nacre-inspired material from a lab at McGill is a great summary of what makes nacre special and what engineers can learn from it.

In Other News

I published a piece in Science Magazine News! It’s about anti-vaccination videos in Portuguese on YouTube.

Turns out the great glider is actually three separate species and, with that, two new marsupial species were discovered in Australia!

“…Noise from dolphins, humans and the tectonic grumblings of the seafloor itself…” are just some of the sounds you’d here if you dropped a hydrophone into the deep sea. Creating a library of sounds could help conservationists know if something is wrong in the deep sea.